Feb 11, 2026

by Nikhil Pai

Most disability cases are won or lost before the hearing starts. The ALJ has already reviewed the file. Opinions have formed. If your evidence is incomplete, disorganized, or submitted late, you're fighting uphill from the moment your client sits down.

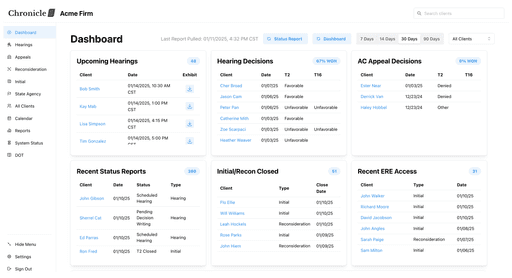

This hearing prep complete guide breaks down the systematic workflow that experienced disability attorneys use to prepare cases for ALJ hearings. Not the claimant-facing basics (what to wear, how to answer questions) but the operational process that determines whether a case is actually ready when it matters.

The ALJ level is where representation pays off most. Claimants with attorneys are three times more likely to win benefits at hearing than those without. But that advantage only holds if preparation is thorough. A missed deadline, an overlooked document in ERE, or a poorly organized medical chronology can undo months of work.

The short version: effective hearing prep follows six steps. Complete file review, medical evidence organization, deadline tracking, hearing brief drafting, client preparation, and day-of execution. Each step has specific timing requirements, and missing any of them creates risk. The sections below break down exactly what each step involves and when it needs to happen.

Why Hearing Prep Is the Make-or-Break Stage

The ALJ hearing has the highest approval rate of any stage in the disability process. More than half of cases that reach hearing result in approval. That's far better odds than initial applications (where 68% are denied) or reconsideration (where denial rates climb even higher).

This isn't because ALJs are more lenient. The hearing is the first time someone with actual decision-making authority looks at the case in full, with testimony, medical evidence, and vocational expert input all in the same room. Done right, it's your best shot at a favorable outcome.

But hearings are also where preparation gaps become visible. The ALJ sees everything: the incomplete treatment history, the missing RFC assessment, the medical records that contradict your client's testimony. Cases don't fail at hearing because the facts are bad. They fail because the file doesn't tell a coherent story, or tells one that wasn't intended.

Eighty-three percent of claimants at ALJ hearings have representation. The question isn't whether to prepare. It's whether your preparation process is systematic enough to catch what matters.

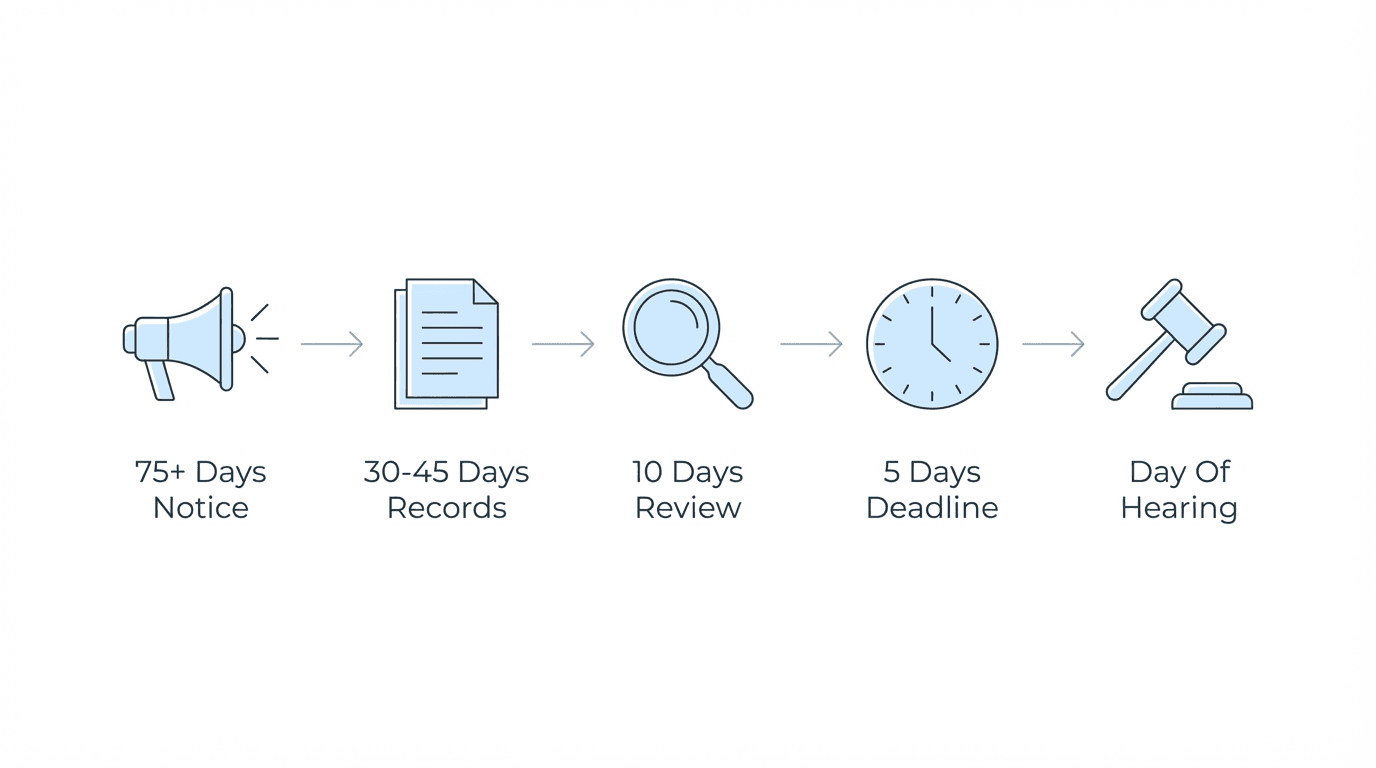

The Hearing Prep Timeline: Key Milestones

Understanding the timeline backwards is the first step to building a reliable workflow. Here's what happens after a hearing is scheduled, and when each milestone requires action:

75+ days before hearing: SSA sends the Notice of Hearing. This is your trigger to begin active preparation. The case file should already be accessible via ERE.

30-45 days before hearing: target window for obtaining updated medical records and treating source statements. Physicians need lead time, and you need time to review what they provide.

10 working days before hearing: the ALJ conducts pre-hearing file review. Any evidence or brief submitted after this point may not be read before the hearing begins. First impressions matter.

7-10 days before hearing: optimal window to submit your hearing brief. Early enough to influence the judge's initial review; late enough to incorporate recent evidence.

5 business days before hearing: hard deadline for evidence submission. SSA requires written evidence no later than five business days prior. Late submissions require showing "good cause," and relying on exceptions is not a strategy.

Day of hearing: final client prep, typically 60-90 minutes before. Cover anticipated questions, review key documents, and address any last-minute concerns.

The judges who decide these cases aren't reviewing files for the first time at the hearing. They're confirming or revising opinions formed during that 10-day pre-hearing review window. Everything you do in preparation is about shaping what they see before your client speaks.

Step 1: Complete Case File Review

The first real work begins with pulling and reviewing the full case file. Once the Request for Hearing is processed, the electronic file becomes accessible through ERE. This is where you see exactly what DDS used to deny the case, and what's missing.

What to look for:

Start with the DDS determination rationale. Understand precisely why the case was denied. Was it a failure to meet a listing? Insufficient evidence of functional limitations? A credibility issue? You can't fix what you haven't diagnosed.

Then verify what medical evidence SSA actually received versus what you thought was submitted. Records get lost. Faxes don't go through. ERE uploads fail silently. This is worth checking even if you're confident.

Look for gaps in treatment history. Long periods without documented care create problems. Either fill those gaps with records from providers you didn't know about, or prepare to address them directly in testimony.

Negative evidence is critical. Notes where a physician says "doing well" or "symptoms controlled." Surveillance reports if there's a workers' comp overlap. Any document that undermines your theory of the case needs to be identified now so you can address it in the brief.

Check for recent SSA correspondence: new notices, updated earnings records, anything that affects the case. These appear in ERE, but only if someone checks.

The file review is where most hearing prep problems start. Not because attorneys don't care, but because ERE requires active monitoring. Documents appear without notification. Staff check when they remember to check, which isn't always often enough.

Firms using Chronicle's automatic ERE monitoring report catching documents they would have missed entirely. New medical evidence from consultative exams, updated earnings records, notices of schedule changes. The system checks every case daily, and when something appears, the right person knows immediately.

Step 2: Medical Evidence Organization

A disorganized medical file is a liability at hearing. The ALJ has limited time. The vocational expert needs clear functional limitations to work with. Your ability to reference specific exhibits during testimony depends on actually knowing what's in them.

Gathering records:

Request updated records from every treating physician, specialist, and facility. Don't assume the file is current just because records were submitted at application. Six to eighteen months may have passed since the initial denial. Treatment has continued. New diagnoses may exist.

Treating source statements:

These carry significant weight. A treating physician's opinion on functional limitations (what the claimant can and cannot do despite their impairments) is often the difference between approval and denial. Request RFC assessments directly. Be specific about what you need: limitations on sitting, standing, walking, lifting, concentration, attendance, and any other work-related functions affected by the condition.

Organization approach:

Sort records by body system or condition, not by provider. The ALJ thinks in terms of impairments and limitations, not in terms of which doctor said what. Create a chronology that shows the progression of the condition, treatment attempts, and functional decline over time.

Bates stamp everything. When you reference Exhibit 4F at pages 15-17 during the hearing, everyone should be able to find it immediately. This seems basic, but disorganized exhibits waste hearing time and frustrate judges.

Chronicle's document organization features handle much of this automatically. Evidence from ERE and physical mail gets centralized, pages get stamped for reference, and chronologies update as new records arrive.

Step 3: Deadline Tracking and Evidence Submission

The five-business-day rule is unforgiving. Evidence submitted after the deadline requires demonstrating "good cause" for late submission, and judges have discretion to exclude late evidence entirely. Relying on exceptions is how cases get lost.

What counts as evidence:

Written evidence includes medical records, treating source statements, RFC assessments, third-party statements, and any other documentation relevant to the claim. If it wasn't in the file before, and you want the ALJ to consider it, submit it before the deadline.

Submission methods:

Electronic submission through ERE is fastest and creates a clear record. Physical mail works but adds transit time and introduces delivery uncertainty. Whatever method you use, confirm receipt. Don't assume.

Why earlier is better:

The five-day deadline is a minimum. Evidence submitted 10-14 days before hearing has a better chance of actually being reviewed during the ALJ's pre-hearing preparation. Late evidence, even if technically on time, may sit unread until the hearing itself.

Tracking across cases:

A single missed deadline can result in malpractice exposure. Multiply that risk across dozens or hundreds of active cases, each with different hearing dates, and the tracking problem becomes real. Calendar reminders help. Spreadsheets help more. But manual systems fail when caseloads grow or staff changes.

Chronicle tracks submission deadlines automatically. Alerts fire before deadlines approach, not after they pass. Firms report zero missed deadlines after implementation. Not because staff became more diligent, but because the system removed the reliance on memory.

Step 4: Drafting the Hearing Brief

The hearing brief is your opportunity to frame the case before the ALJ hears testimony. Done well, it shapes how the judge interprets the evidence. Done poorly, or not at all, it leaves interpretation to chance.

Purpose of the brief:

Judges conduct file reviews roughly 10 working days before hearing. A well-timed brief becomes part of that review. It tells the judge what to focus on, how to interpret the medical evidence, and why the case meets disability standards. Think of it as opening argument in written form.

Covering the five-step evaluation:

Every disability determination follows SSA's five-step sequential evaluation. Your brief should address each step, even if briefly:

Is the claimant engaging in substantial gainful activity?

Does the claimant have a severe impairment?

Does the impairment meet or equal a listed impairment?

Can the claimant perform past relevant work?

Can the claimant perform any other work in the national economy?

Don't assume the judge will connect the dots. Spell out your theory of the case at each step. Cite specific exhibits. Reference page numbers.

Addressing negative evidence:

This is where many briefs fail. Ignoring unfavorable evidence doesn't make it disappear. The judge discovers it without your context. If there's a note in the file saying your client's condition is "well controlled," address it. Explain why that notation doesn't reflect the full picture. Anticipate the objection and defuse it.

Tailoring to the ALJ:

Some judges focus heavily on vocational issues. Others scrutinize medical opinions. If you know who's assigned to the case, consider what that judge typically emphasizes and adjust your brief accordingly. This isn't manipulation. It's effective advocacy.

Step 5: Client Preparation

Even the best-documented case can fail if the client's testimony contradicts the evidence or comes across as vague and unreliable. Client preparation isn't coaching. It's ensuring your client understands what they'll be asked and how to answer honestly and effectively.

Pre-hearing meeting:

Schedule 60-90 minutes with your client before the hearing. Walk through the format: who will be present, what order questions typically follow, how long the hearing usually lasts. Reduce anxiety by eliminating uncertainty.

Question categories to rehearse:

ALJs typically ask about:

- Daily activities and functional limitations

- Work history and why past jobs are no longer possible

- Medical treatment, medications, and side effects

- Specific physical or mental limitations (walking distance, sitting duration, concentration, etc.)

Practice answering with specificity. "I can walk about 20 yards before I need to stop, roughly the length of my driveway" is far better than "not very far." Vague answers invite skepticism.

Handling difficult questions:

Some questions seem designed to elicit problematic answers. "What did you do yesterday?" "Do you help with chores?" These aren't tricks. They're attempts to understand daily functioning. Prepare your client to answer honestly while providing context. "I helped with dishes, but I had to sit down twice because of back pain" is truthful and informative.

What to avoid:

Minimizing symptoms to appear stoic backfires. So does exaggerating. Inconsistency between testimony and medical records is the fastest way to lose credibility. Review the file with your client so they understand what's documented and can testify consistently.

Step 6: Day-of and Post-Hearing Protocol

The hearing itself is typically 30-60 minutes. Most occur by phone or video now, though in-person hearings still happen. Regardless of format, the final preparation matters.

Final document check:

Confirm your client has identification. Ensure you have copies of key exhibits for reference. If the hearing is remote, test the connection in advance.

During the hearing:

Listen carefully to vocational expert testimony. The hypotheticals the ALJ poses to the VE often reveal how the judge is thinking about the case. Be prepared to pose your own hypotheticals that incorporate your client's specific limitations.

Requesting favorable decisions:

When the evidence strongly supports approval (past work is clearly precluded, or a listing is obviously met) consider requesting a bench decision or on-the-record approval. Not every case qualifies, but when the record is complete and compelling, asking for immediate decision can save months of waiting.

Post-hearing submissions:

Sometimes issues arise during testimony that require additional evidence. If the ALJ leaves the record open, submit whatever's needed promptly. Don't let post-hearing deadlines slip.

The wait:

Decisions typically take 6-8 weeks after hearing. Manage client expectations. Have a plan for appeals if the outcome is unfavorable.

Common Hearing Prep Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

After handling enough hearings, patterns emerge. The same mistakes recur across firms, often because workflows don't account for them.

Submitting evidence late or not at all: usually a tracking failure, not negligence. The deadline passed because no one flagged it in time.

Missing new ERE documents: SSA uploads documents without notification. Consultative exam reports, updated earnings records, notice changes. All appear in ERE silently. Manual checking catches some. Automated monitoring catches all.

Failing to address negative evidence: hope is not a strategy. If it's in the file, the judge will see it.

Vague or inconsistent client testimony: preparation prevents this. One meeting before the hearing isn't enough for complex cases.

Outdated medical statements: RFC assessments from 18 months ago don't reflect current functioning. Request updates.

Not checking ERE during portal outages: when ERE goes down, many firms simply wait. Meanwhile, deadlines continue. Chronicle monitors portal status and continues checking every two hours during outages, ensuring nothing slips through.

Scaling Hearing Prep Without Adding Headcount

Here's the math problem: more cases means more hearings, which means more preparation time. If every step requires manual attention, growth requires proportional staffing increases. The margins don't support it.

The bottleneck isn't attorney capacity. It's administrative workflow. Checking ERE, organizing documents, tracking deadlines, confirming submissions. These tasks multiply with volume but don't require legal judgment. They require reliable systems.

Firms that have systematized hearing prep report handling significantly larger caseloads without proportional staff increases. Viner Disability Law scaled from 900 to 3,000 active cases without adding headcount by automating ERE monitoring and deadline tracking. Ficek Law reports zero missed deadlines since implementing systematic monitoring. These aren't outliers. They're what happens when the administrative friction gets removed.

Chronicle was built specifically for this shift. Continuous ERE monitoring replaces manual portal checks. Automated deadline alerts replace calendar reminders. Centralized document management replaces scattered files. The preparation workflow becomes repeatable and reliable, regardless of case volume.

Hearing Prep Checklist

Use this as a reference for each case approaching hearing:

Upon receiving Notice of Hearing:

- Confirm hearing date and format (phone, video, in-person)

- Access full case file via ERE

- Review DDS determination and identify denial rationale

- Flag missing medical records

- Identify negative evidence requiring response

30-45 days before hearing:

- Request updated records from all treating providers

- Obtain current treating source statements and RFC assessments

- Organize evidence by impairment/body system

- Bates stamp all exhibits

7-14 days before hearing:

- Draft and submit hearing brief

- Confirm all evidence submitted to SSA

- Schedule client preparation meeting

5 business days before hearing:

- Final evidence submission deadline. Confirm receipt.

- Verify no new documents appeared in ERE

Day before hearing:

- Client preparation meeting

- Review key exhibits and anticipated questions

- Confirm technology setup for remote hearings

Post-hearing:

- Submit any additional evidence if record left open

- Document hearing outcomes and next steps

Frequently Asked Questions

How long before a hearing should I start preparing?

Active preparation should begin as soon as the Notice of Hearing arrives, typically 75+ days before the scheduled date. Ongoing case monitoring (including ERE checks) should be continuous from representation through decision. Waiting until the hearing is imminent creates unnecessary risk.

What's the most common reason cases fail at the ALJ level?

Incomplete medical evidence and poorly prepared testimony account for most failures. The file doesn't support the claimed limitations, or the client's testimony contradicts the documented record. Both problems are preventable. Systematic preparation catches the evidence gaps; thorough client meetings address the testimony issues.

Can I submit evidence after the 5-business-day deadline?

Technically yes, but you must demonstrate "good cause" for late submission. Judges have discretion to exclude late evidence entirely. Building a workflow around deadline compliance eliminates this risk. Relying on the exception makes the exception your strategy.

How do I handle negative evidence in the file?

Address it directly in your hearing brief. Explain the context, provide counter-evidence, or reframe the significance. Ignoring negative evidence doesn't make it disappear. The judge encounters it without your interpretation, which is worse.

What if new medical records appear in ERE right before the hearing?

Review them immediately. If they support your case, incorporate them into your preparation. If they create problems, adjust your brief or testimony strategy accordingly. Automated ERE monitoring ensures you see new documents as soon as they appear. Without it, discovery often comes too late.

Hearing preparation isn't complicated in concept. Review the file, organize the evidence, hit the deadlines, prepare the client. The challenge is doing this reliably across dozens or hundreds of cases, each with different timelines and requirements.

The firms that win consistently aren't working harder. They've built systems that make thorough preparation the default outcome rather than a heroic effort. Chronicle provides the infrastructure for that kind of practice: continuous monitoring, automated deadlines, centralized evidence. The workflow this guide describes becomes not just possible, but sustainable.

If your current process relies on memory, manual checks, and hoping nothing slips through, there's a better way to operate.